How teams decide to deploy software is an important consideration before starting the software development process.

This means long before the code is written and tested, teams need to carefully plan the deployment process of new features and/or updates to ensure it won’t negatively impact the user experience.

Having an efficient deployment strategy in place is crucial to ensure that high quality software is delivered in a quick, efficient, consistent and safe way to your intended users with minimal disruptions.

In this article, we’ll go through what a deployment strategy is, the different types of strategies you can implement in your own processes and the role of feature flags in successful rollouts.

What is a deployment strategy?

A deployment strategy is a technique adopted by teams to successfully launch and deploy new application versions or features. It helps teams plan the processes and tools they will need to successfully deliver code changes to production environments.

It’s worth noting that there’s a difference between deployment and release though they may seem synonymous at first.

Deployment is the process of rolling out code to a test or live environment while release is the process of shipping a specific version of your code to end-users and the moment they get access to your new features. Thus, when you deploy software, you’re not necessarily exposing it to real-world users yet.

In that sense, a deployment strategy is the process by which code is pushed from one environment into another to test and validate the software and then eventually release it to end-users. It’s basically the steps involved in making your software available to its intended users.

This strategy is now more important than ever as modern standards for software development are demanding and require continuous deployment to keep up with customer demands and expectations.

Having the right strategy will help ensure minimal downtime and will reduce the risk of errors or bugs so users get the best experience possible. Otherwise, you may find yourself dealing with high costs due to the number of bugs that need to be fixed resulting in disgruntled customers which could severely damage your company’s reputation.

Types of deployment strategies

Teams have a number of deployment strategies to choose from, each with their own pros and cons depending on the team objectives.

The deployment strategy an organization opts for will depend on various factors including team size, the resources available as well as how complex your software is and the frequency of your deployment and/or releases.

Below, we’ll highlight some of the most common deployment strategies that are often used by modern software development and DevOps teams.

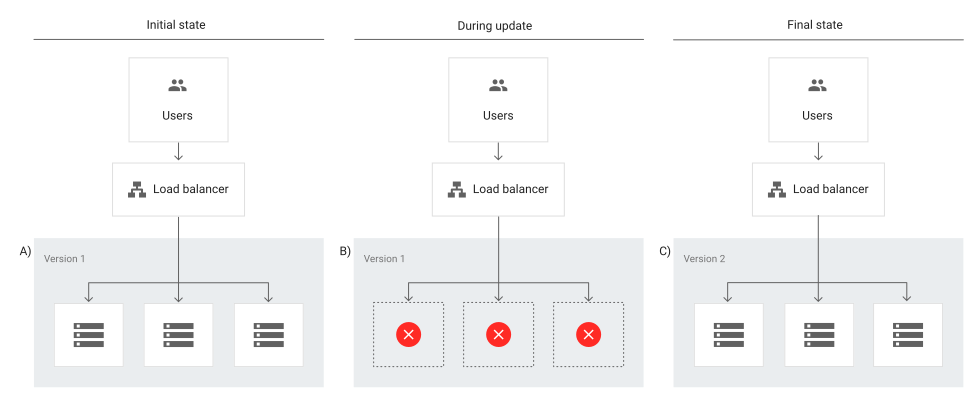

Recreate deployment

A recreate deployment strategy involves developers scaling down the previous version of the software to zero in order to be removed and to upload a new one. This requires a shutdown of the initial version of the application to replace it with the updated version.

This is considered to be a simple approach as developers only have to deal with one scaling process at a time without having to manage parallel application deployments.

However, this strategy will require the application to be inaccessible for some time and could have significant consequences for users. This means it’s not suited for critical applications that always need to be available and works best for applications that have relatively low traffic where some downtime wouldn’t be a major issue.

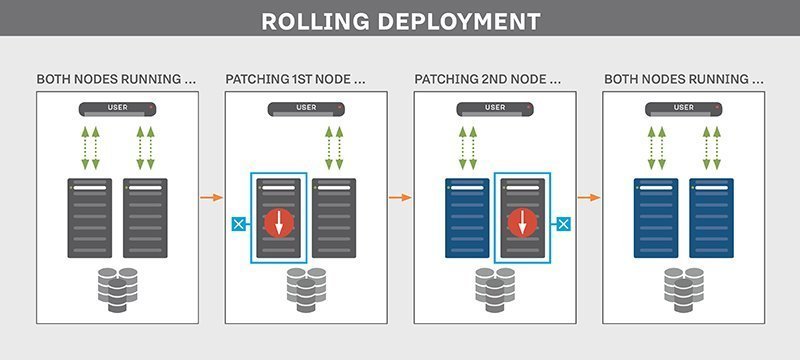

Rolling deployment

A rolling deployment strategy involves updating running instances of the software with the new release.

Rolling deployments offer more flexibility in scaling up to the new software version before scaling down the old version. In other words, updates are rolled out to subsets of instances one at a time; the window size refers to the number of instances updated at a time. Each subset is validated before the next update is deployed to ensure the system remains functioning and stable throughout the deployment process.

This type of deployment strategy prevents any disruptions in service as you would be updating incrementally- which means less users are affected by any faulty update- and you would then direct traffic to the updated deployment only after it’s ready to accept traffic. If any issue is detected during a subset deployment, it can be stopped while the issue is fixed.

However, rollback may be slow as it also needs to be done gradually.

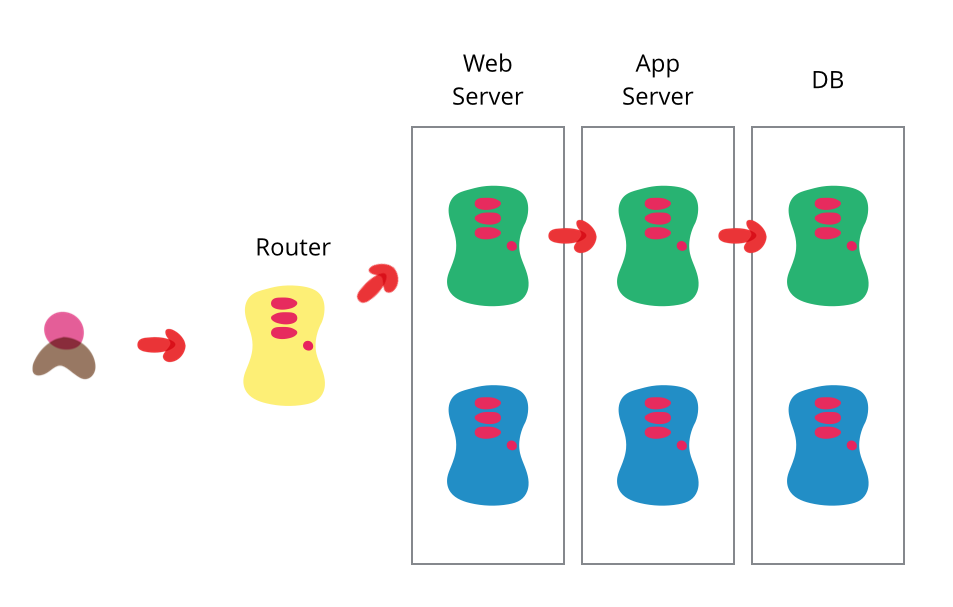

Blue-green deployment

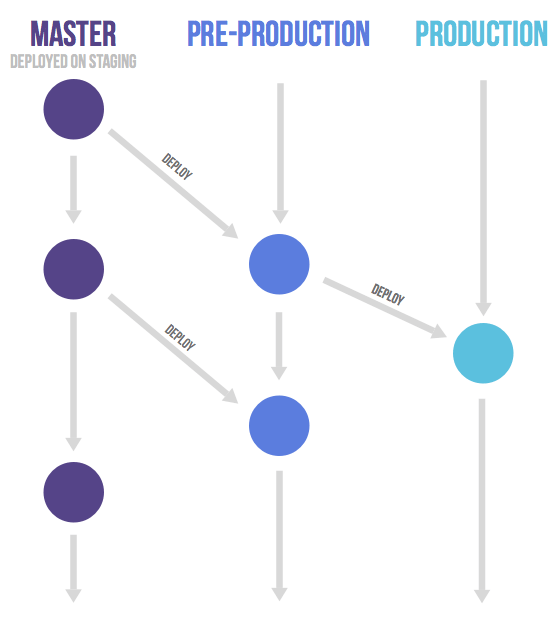

A blue/green deployment strategy consists of setting up two identical production environments nicknamed “blue” and “green” which run side-by-side, but only one is live, receiving user transactions. The other is up but idle.

Thus, at any given time, only one of them is the live environment receiving user transactions- the green environment that represents the new application version. Meanwhile, teams use the idle blue system as the test or staging environment to conduct the final round of testing when preparing to release a new feature.

Afterwards, once they’ve validated the new feature, the load balancer or traffic router switches all traffic from the blue to the green environment where users will be able to see the updated application.

The blue environment is maintained as a backup until you are able to verify that your new active environment is bug-free. If any issues are discovered, the router can switch back to the original environment, the blue one in this case, which has the previous version of the code.

This strategy has the advantage of easy rollbacks. Because you have two separate but identical production environments, you can easily make the shift between the two environments, switching all traffic immediately to the original (for example, blue) environment if issues arise.

Teams can also seamlessly switch between previous and updated versions and cutover occurs rapidly with no downtime. However, for that reason this strategy may be very costly as it requires a well-built infrastructure to maintain two identical environments and facilitate the switch between them.

Canary deployment

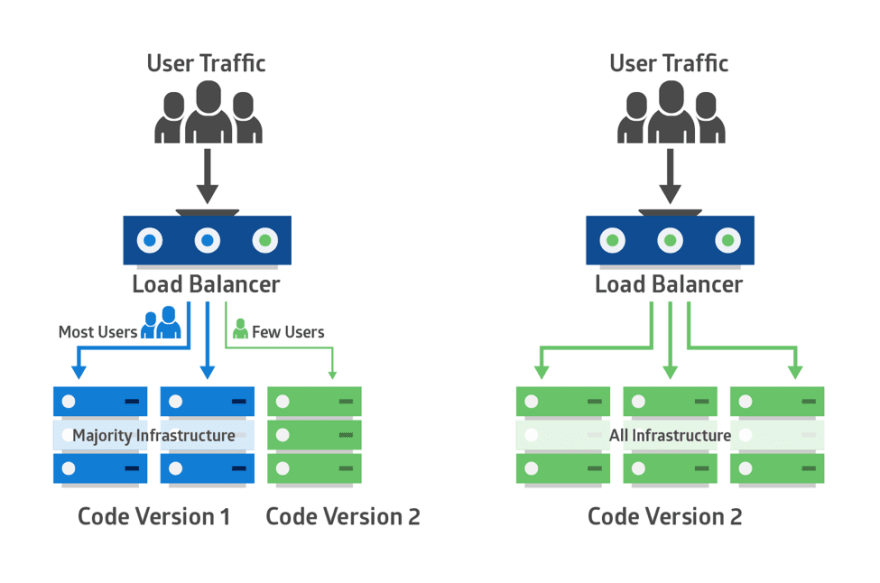

Canary deployments is a strategy that significantly reduces the risk of releasing new software by allowing you to release the software gradually to a small subset of users. Traffic is directed to the new version using a load balancer or feature flag while the rest of your users will see the current version

This set of users identifies bugs, broken features, and unintuitive features before your software gets wider exposure. These users could be early adopters, a demographically targeted segment or a random sample.

Therefore, you start testing on this subset of users then as you gain more confidence in your release, you widen your release and direct more users to it.

Canary deployments are less risky than blue-green deployments as you’re adopting a gradual approach to deployment instead of switching from one environment to the next.

While blue/green deployments are ideal for minimizing downtime and when you have the resources available to support two separate environments, canary deployments are better suited for testing a new feature in a production environment with minimal risk and are much more targeted.

In that sense, canary deployments are a great way to test in production on live users but on a smaller scale to avoid the risks of a big bang release. It also has the advantage of a fast rollback should anything go wrong by redirecting users back to the older version.

However, deployment is done in increments, which is less risky but also requires monitoring for a considerable period of time which may delay the overall release.

A/B testing

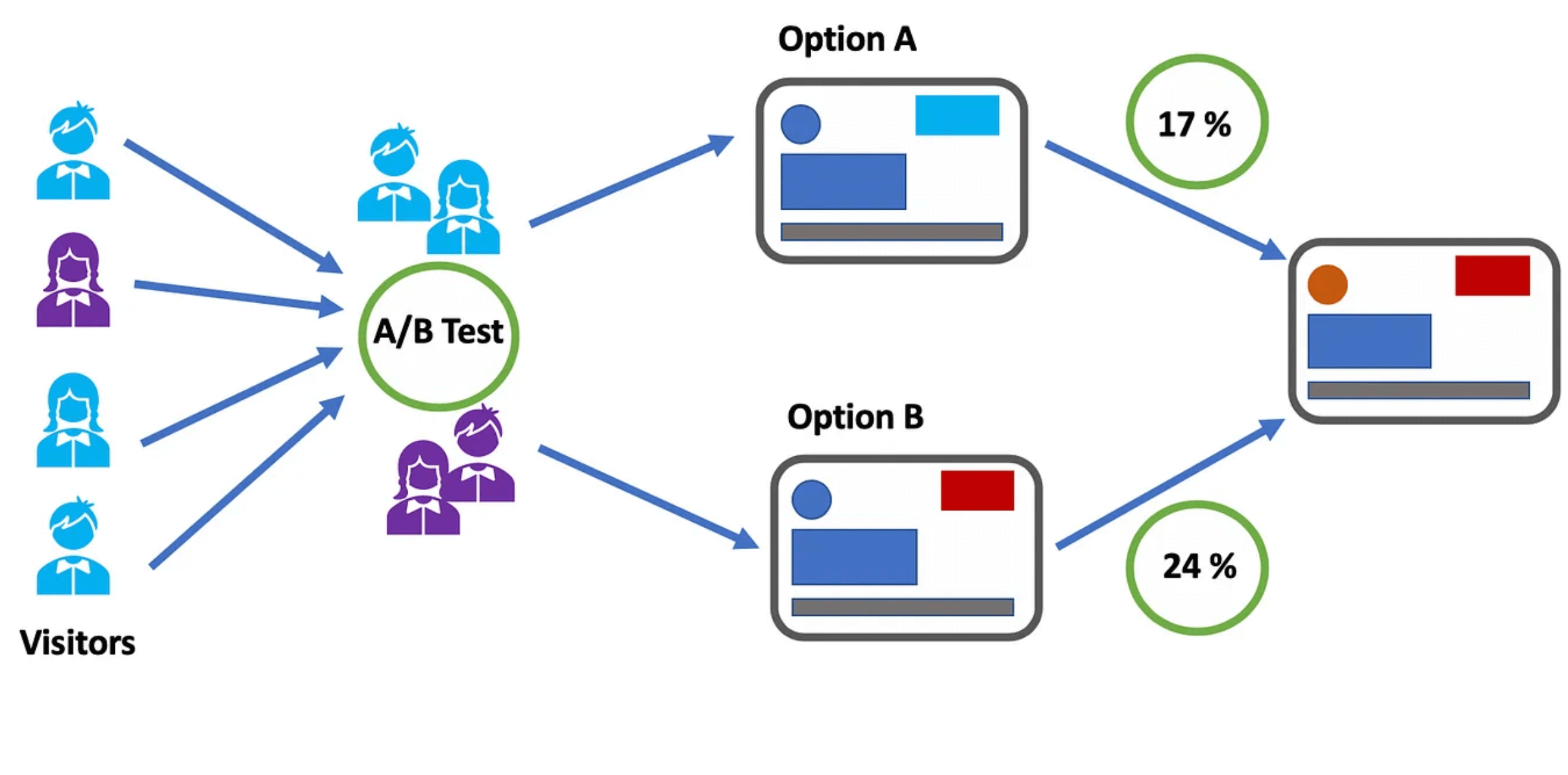

A/B testing, also known as split testing, involves comparing two versions of a web page or application to see which performs better, where variations A and B are presented randomly to users. In other words, users are divided into two groups with each group receiving a different variation of the software application.

A statistical analysis of the results then determines which version, A or B, performed better, according to certain predefined indicators.

A/B testing enables teams to make data-driven decisions based on the performance of each variation and allows them to optimize the user experience to achieve better outcomes.

It also gives them more control over which users get access to the new feature while monitoring results in real-time so if results are not as expected, they can redirect visitors back to the original version.

However, A/B tests require a representative sample of your users and they also need to run for a significant period to gain statistically significant results. Moreover, determining the validity of the results without a knowledge database can be challenging as several factors may skew these results.

AB Tasty is an example of an A/B testing tool that allows you to quickly set up tests with low code implementation of front-end or UX changes on your web pages, gather insights via an ROI dashboard, and determine which route will increase your revenue.

Feature flags: The perfect companion for your deployment strategy

Whichever deployments you choose, feature flags can be easily implemented with each of these strategies to improve the speed and quality of the software delivery process while minimizing risk.

By decoupling deployment from release, feature flags enable teams to choose which set of users get access to which features to gradually roll out new features.

For example, feature flags can help you manage traffic in blue-green deployments as they can work in conjunction with a load balancer to manage which users see which application updates and feature subsets.

Instead of switching over entire applications to shift to the new environment all at once, you can cut over to the new application and then gradually turn individual features on and off on the live and idle systems until you’ve completely upgraded.

Feature flags also allow for control at the feature level. Instead of rolling back an entire release if one feature is broken, you can use feature flags to roll back and switch off only the faulty feature. The same applies for canary deployments, which operate on a larger scale. Feature flags can help prevent a full rollback of a deployment; if anything goes wrong, you only need to kill that one feature instead of the entire deployment.

Feature flags also offer great value when it comes to running experiments and feature testing by setting up A/B tests by allowing for highly granular user targeting and control over individual features.

Put simply, feature flags are a powerful tool to enable the progressive rollout and deployment of new features, run A/B testing and test in production.

What is the right deployment strategy?

Choosing the right deployment strategy is imperative to ensure efficient, safe and seamless delivery of features and updates of your application to end-users.

There are plenty of strategies to choose from, and while there is no right or wrong choice, each comes with its own advantages and disadvantages.

Whichever strategy you opt for will depend on several factors according to the needs and objectives of the business as well as the complexity of your application and the type of targeting you’re looking to implement i.e whether you want to test a new feature on a select group of users to validate it before a wider release.

No matter your deployment strategy, AB Tasty is your partner for easier and low risk deployments with Feature Experimentation and Rollouts. Sign up for a free trial to explore how AB Tasty can help you improve your software delivery processes.